Ok we know: Not everyone believes in Santa.

But, late on Christmas Eve, I heard sleigh bells ring and a rustling on our roof. The very next day, I found white hair strands at the roof, that looked suspiciously like Santa’s beard hair. Did Father Christmas pay us a visit? Did the hair come from someone else, or worse, was it from a fake Santa’s beard?!

To unravel this mystery, I set out on a quest for clues. And what could be better suited for this than FTIR spectroscopy?

Hair analysis by FTIR is nothing unusual

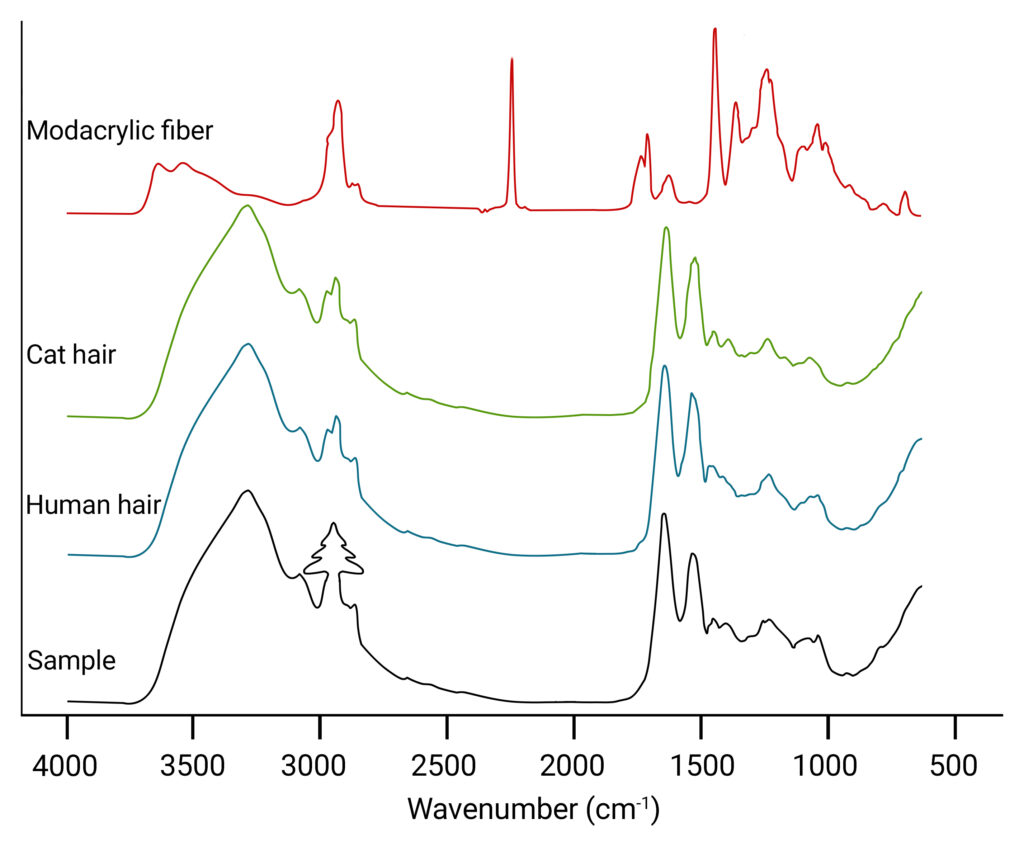

In forensic science, infrared spectroscopy is traditionally used to identify hair or other fibers. And as I felt like a little bit of a forensic scientist myself in this case, I used the ALPHA II in ATR mode for this special analysis. The measurement only took a few moments and a comparison with our spectral libraries showed several possible hits (see image below)

So let’s see who our possible suspects are!

Fake Santa wig

In red we see a spectra of modacrylic fiber. This synthetic copolymer is commonly used in artificial wigs because it is very durable, non-allergenic, and most importantly very lifelike. That the hair could theoretically stem from a fake beard is not entirely implausible.

These days, many ‚false‘ Santa’s roam around in shopping malls and Christmas markets. However, when we take a closer look at the spectrum, differences emerge compared to our sample. For instance, the analyzed sample lacks the pronounced peak at 2260 cm-1, which corresponds to the C≡N stretching vibration. Thus we can rule out the fake Santa as a suspect. Besides, what could someone except Santa be doing on our roof at night anyway?“

Human and cat hair

The data comparison also flagged human and cat hair as possible hits. In fact both would be very likely. My dad has a white beard and actually bears a suspicious resemblance to Santa. And we also have a white cat, Porthos, who really enjoys climbing around on the roof.

When comparing the human and cat hair with our sample, we see clear similarities. Natural hair mainly consists of proteins. Amide bands are a typical indicator for these proteins and are observed in the region of 1500 to 1700 cm-1 in the spectrum. Bands in the region of 2800 to 3000 cm⁻¹ are associated with C-H stretching vibrations.

They can provide information about the hydrocarbon chains in lipids and proteins. Bands in the region of 1000 to 1300 cm⁻¹ are associated with C-O stretching vibrations in carbohydrates and the O-H bending vibration in water.

But wait!

Have you noticed the one straddling difference in the spectra? The shape of the peak at 2940 cm-1! It shows a clearly recognizable Christmas tree shape!

If that’s not proof that Santa Claus visited us – I don’t know what could be!

Conclusion

In conclusion, the ALPHA II effectively differentiates the real Santa’s beard from potential imitations or other natural hair. By ruling out synthetic fibers, it suggests human and cat hair as likely sources of the hair found on our roof. The distinctive Christmas tree shape in the spectra however could be used to confirm that it was Santa who visited our house late on Christmas Eve.

As you can see, the ALPHA II proves invaluable even for the most unconventional forensic inquiries.

Would you like to know more about artificial vs. natural hair and fibers? Go ahead and read our blog article about counterfeit textile characterization: